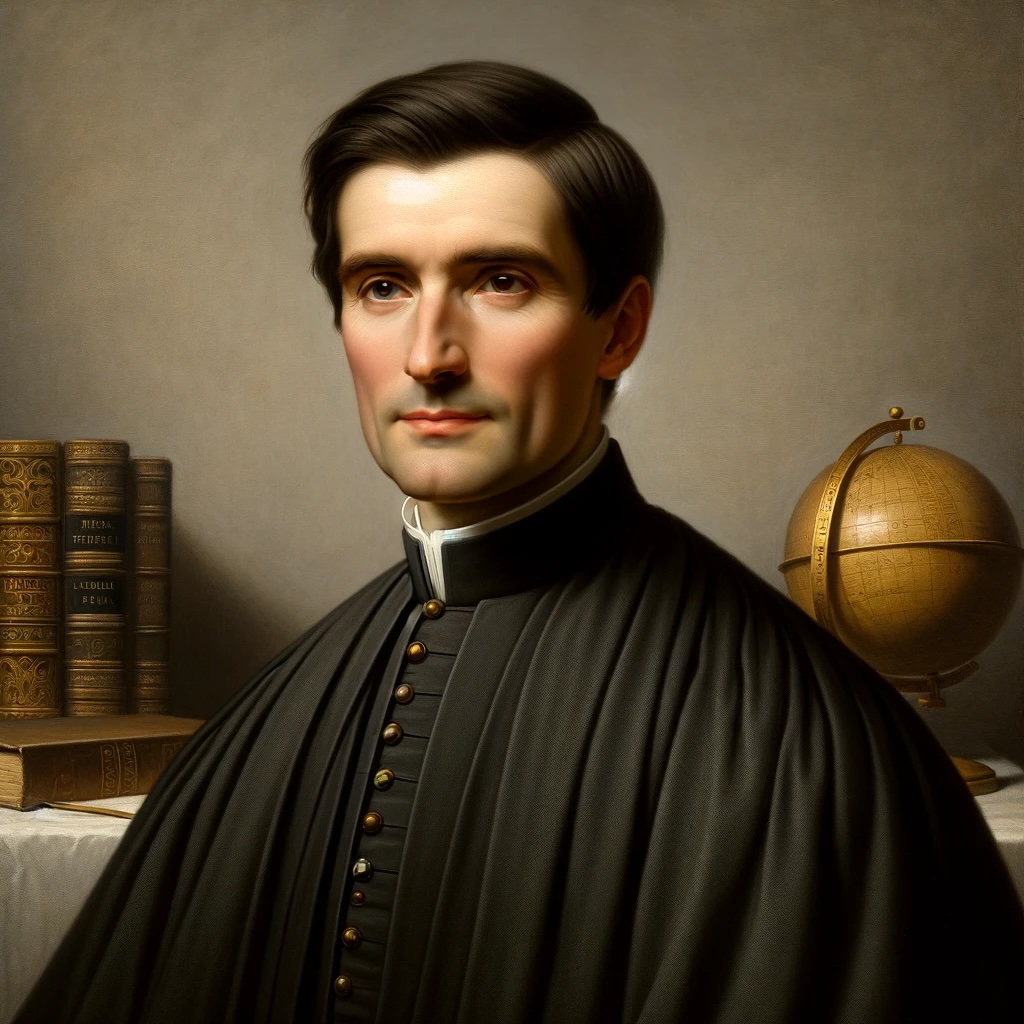

One of the prominent figures in the Spanish Renaissance was Francisco de Vitoria (1483-1546). He was a Spanish Dominican, renewer of Theology and promoter of the Salamanca School of Natural Law. He is considered the founder of the science of International Law and the notion of human rights. One of the most relevant political philosophers of the 20th century, John Rawls, in his book entitled Law of Peoples and the Idea of Public Reason revisited quotes De Vitoria and, from a liberal conception, adheres to his just war theory.

Precisely Francisco de Vitoria addresses this classic theme in his essay entitled ” Sobre el derecho de Guerra”/ On the law of war when he asks: “What can be the reason and cause of a just war?” We will address this question below, based on this author, from the perspective of Minerva Strategy Blog.

De Vitoria’s first approach to answering this question states that “diversity of religion is not sufficient cause for a just war.” And he justifies himself with that “even if the faith has been announced to the barbarians with sufficient signs of probability and they have not wanted to accept it, it is not, for that reason, lawful to persecute them with war and strip them of their goods” (Francisco de Vitoria, Sobre los indios, II.15).

Francisco de Vitoria was a professor at the University of Salamanca and his lectures, or relections, on various topics of interest have come down to us to this day. Specifically, the full title of the one dedicated to the notion of just war is entitled: ” Sobre el derecho de guerra de los españoles sobre los bárbaros”/On the law of war of the Spaniards over the barbarians. Contrary to what the black legend on the Spanish colonisation of Latin America claims, the School of Salamanca laid the foundations for human rights and the rules of International Law. And, as has been seen, De Vitoria did not justify war for diversity of religion.

Another issue addressed by Francisco de Vitoria is that “it is not a just cause of a war to intend to expand dominions” and he argues: “this proposition is too evident to need to be demonstrated. For otherwise there would always be just cause for any of the belligerent wars, and so all would be innocent” (Francisco de Vitoria, Sobre el derecho de guerra, III.11).

The history of mankind contains many examples of rulers who have had expansionist policies beyond their borders. The results of these offensive wars are part of History and memory. This would not be a justified strategy under current International Law, nor as a cost/benefit analysis in the medium and long term.

Francisco de Vitoria continues “neither is it just cause of a war to the prince’s own glory nor any other particular profit of the prince” and he states that “this proposition is also evident, for the prince must order to the common good of the Republic, both war and peace, and he cannot invest public funds in his own glory, in his own profit, much less expose his subjects to danger. The difference between the legitimate king and a tyrant lies in that the tyrant orders the government to his own interest and profit, while the king orders it to the public good, as Aristotle says” (Francisco de Vitoria, Sobre el derecho de guerra, III.12).

If the ruler wages war for his private benefit, he becomes a tyrant, as Aristotle argued in his work Politics. There the Stagirite philosopher proposed a classic typology of forms of government, where he distinguishes those leaders who promote the common good in their government actions -monarchy, aristocracy, politeia– and those who act for their own benefit or that of their own group -tyranny, oligarchy, democracy-. It is interesting because issues of accountability have been identified ever since the first book written on Political Science, which deals especially with issues of classical democracy in the polis of Athens.

The affirmative answer to the question posed by De Vitoria is the following: “the only just cause for waging war is the injury received” and he affirms that “in addition, offensive war is made to avenge an injury and to reprimand the enemies, as has already been said. But there can be no revenge where there has not preceded an injury and a fault. Therefore the conclusion is evident” (Francisco de Vitoria, Sobre el derecho de guerra, III.13).

Here we get to the heart of Francisco de Vitoria’s argument: defensive war, self-defence, is justified. Bobbio affirms: “it is lawful to repel violence with violence.” The Italian author asks himself: “But does the strategy of atomic war still allow us to maintain the distinction between offensive and defensive war?” (Norberto Bobbio, El problema de la guerra y las vías de la paz). De Vitoria did not speak of preventive wars, but in the answer to Bobbio it is worth analising whether a preventive war is justified in the face of a relevant threat. Situations of strategic funanbulism in scenarios of nuclear deterrence are placed in this risk analysis.

Francisco de Vitoria adds: “an injury of any gravity is not enough to make war”. He clarifies that “this proposition is proved because it is not even lawful to impose such serious penalties as death, exile or confiscation of goods on one’s own subjects for any fault. Now, since all the things that are done in war are grave and even atrocious, such as slaughter, arson, devastation, it is not lawful to punish with war those who have committed slight offences, since the measure of punishment must be in accordance with the gravity of the crime” (Francisco de Vitoria, Sobre el derecho de guerra, III.14).

The key to self-defence is proportionality. Thomas Aquinas already defended it by “moderating the defence according to the needs of the threatened security” (Thomas Aquinas, Suma Theologica, II-II, q. 64,a. 7, c). It is in that passage of the Theological Summa, where the theory of the double effect is formulated: an act has two effects, one intentional -preserving life- and another not, which would be incidental -the death of the aggressor-. The key for Thomas Aquinas is that the act be proportionate to its end.

An application of the doctrine of double effect is proposed by Rawls, when he states that civilian casualties are prohibited except insofar as they are the indirect and unintended result of a legitimate attack against a military target (Rawls, Law of Peoples and the Idea of Public Reason revisited).

The just war theory in Francisco de Vitoria is a classic in the reflection on public affairs. As a good classic, it allows more current re-readings and, as Italo Calvino said, it can be conceived as a talisman, a compass on which to orient oneself when approaching the territories of peace and war.