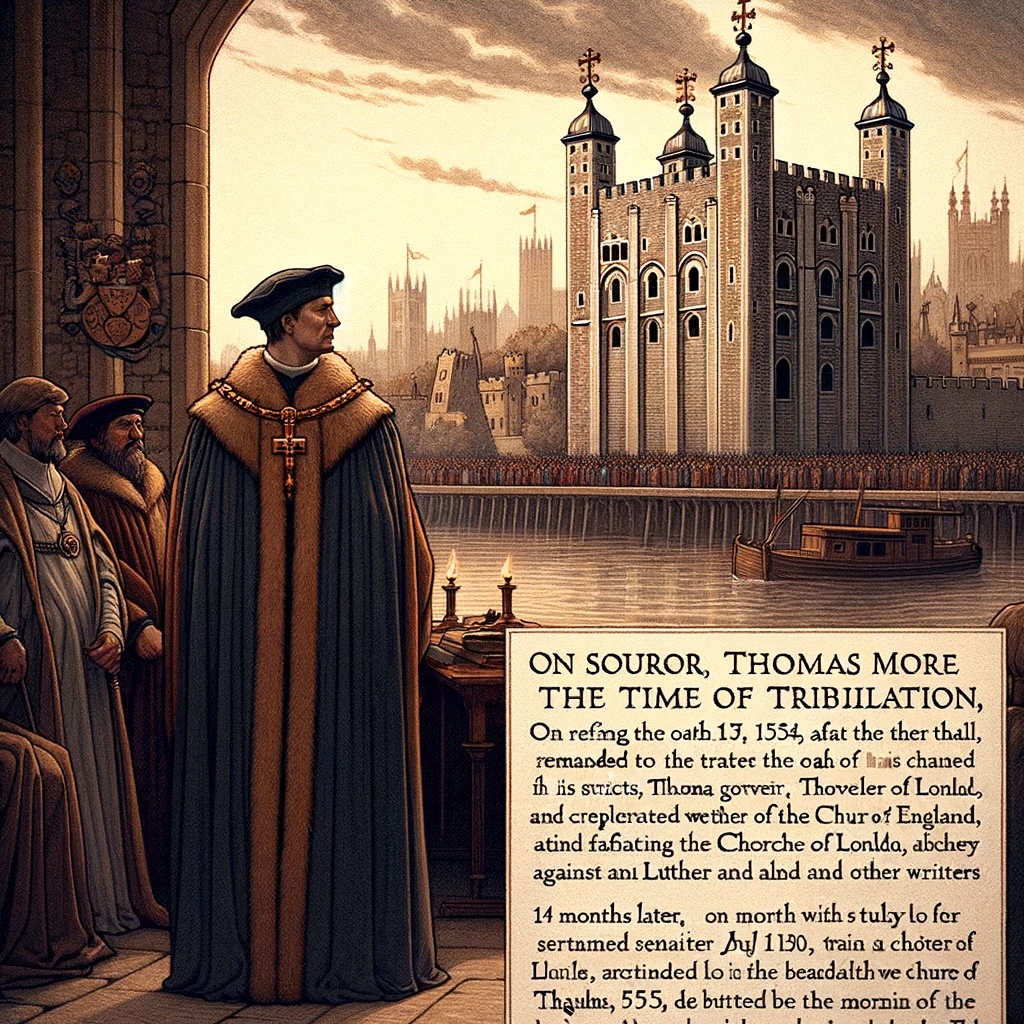

In 1534, Thomas More (1478-1535), well-known author of the work Utopia and defender of Catholic orthodoxy against Luther and other writers, was captured in the Tower of London by the Thames after refusing the oath that King Henry VIII demanded from his subjects to grant him the title of Supreme Head of the Church of England. After 14 months, on 1 July 1535, he was put on trial and sentenced to death, and executed in the morning of 6 July.

Thomas More wrote several works during those months, including A Dialogue on Comfort against Tribulation, in which he stands firm in his convictions that have led him to the Tower of London, where he has lost his position and may lose his life. It is a book that makes many religious references and can be seen as an exercise in affirmation in the face of hard times. It also provides recommendations and great wisdom, which will be analysed below with the focus of the Minerva Strategy.

“But this arrow of pride, fly it never so high in the clouds, and be the man that it carrieth up so high never so joyful thereof… yet let him remember… that be this arrow never so light, it hath yet a heavy iron head… and therefore, fly it never so high… down must it needs come and on the ground must it light… and falleth, sometimes, not in a very clean place… but the pride turneth into rebuke and shame, and there is then all the glory gone.” (More, Thomas. A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, II.16).

The Spanish Royal Academy of Language defines pride as “haughtiness and disordered appetite to be preferred to others”, while it can also be defined as “satisfaction and conceit by the contemplation of one’s own prerogatives with contempt for others”. Pride is a bad strategy because it can ruin interpersonal relationships, cause a lack of empathy and make it difficult to learn.

In some contexts and sectors, this human attitude is encouraged that avoids putting oneself in the other’s place and is the opposite of humility. It can be considered an obstacle to the good management of emotions and good relationships with others.

“Hard is it, Cousin, in many manner things, to bid or forbid, affirm or deny, reprove or allow, a matter nakedly proposed and put forth; or precisely to say “This thing is good,” or “This thing is naught,” without consideration of the circumstances.” (More, Thomas. A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, II.17).

This recalls Ortega y Gasset’s famous phrase “Yo soy yo y mi circunstancia” (I am I and my circumstance) found in his work Meditaciones del Quijote – Meditations on the Quijote, published in 1914. The complete sentence, which is often quoted incompletely, is: “I am I and my circumstance, and if I do not save her, I do not save myself”. With this phrase, Ortega means that we cannot achieve fulfillment as individuals if we do not engage with our environment and strive to improve it.

In the case of Thomas More, it refers to the level of ethics and Law, which must take into account the circumstances of the particular case. This is related to the dichotomy between universalism and particularism, as well as the importance of the possibility that general solutions can be reinterpreted according to new circumstances.

“We shall yet, Cousin, consider in these outward “goods of fortune,” as richesse… good name… honest estimation… honorable fame, and authority— in all these things we shall, I say, consider… that either we love them and set by them as things commodious unto us for the state and condition of this present life… or else as things that we purpose by the good use thereof to make them matter of our merit, with God’s help, in the life after to come. Let us, then, first consider them as things set by and beloved for the pleasure and commodity of them for this present life.” (More, Thomas. A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, III.9).

In today’s digital age, it is possible to reinterpret the good name, honour and honourable fame. It is necessary to reconceptualise the terms private, public and intimate. However, it seems that slander, disinformation, rumors and fake news are gaining ground. The worst thing is that there seems to be no standards for verifying news and everything goes.More than ever, Philosophy is necessary.

“And into this pleasant frenzy of much foolish vainglory be there some men brought sometimes by such as themselves do, in a manner, hire to flatter them, and would not be content if a man should do otherwise…but would be right angry, not only if a man told them truth when they do naught indeed… but also if they praise it but slenderly.” (More, Thomas. A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, III.10).

It is common to find professional sycophants who constantly praise everything they receive from their superiors. A minimum level of politeness and courtesy is granted to avoid ungratefulness. However, in professional contexts, it is good to be able to express critical views. If one is a boss, it is important to empower others in a positive way and never denigrate or humiliate them.

“Let us now consider in like wise what great worldly wealth ariseth unto men by great offices, rooms, and authority—to those worldly-disposed people, I say, that desire them for no better purpose” (More, Thomas. A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, III.11)

Thomas More played significant roles in England during the reign of Henry VIII, who chose to establish the Church of England and separate from the Catholic Church for his own benefit. Thomas More chose to remain true to his beliefs, leave his offices and disobey the sovereign. More’s hierarchy of values and the importance he places on office explain this.

“The greatest grief that is in bondage or captivity is this, as I trow: that we be forced to do such labor as with our good will we would not. But then against that grief Seneca teacheth us a good remedy: “Semper da operam ne quid invitus facias”—“Endeavor thyself evermore that thou do nothing against thy will. . . . But that thing that we see we shall needs do… let us use always… to put our good will thereto” (More, Thomas. A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, III.18).This point is fundamental in Thomas More’s tragedy, but it can also have a significant impact in professional and personal contexts. On the one hand, extremely unjust actions can be opposed, which is a classic theme in the Philosophy of Law. Nevertheless, there are many things that we do not want to do, and paradoxically to his story, Moro advises that we put our good will to do them. It is a way to overcome tribulation.